A Kick in the Pants: Q&A with Richard Fulco

Ever notice how most popular novels are about compelling characters with exciting lives? We love those characters, love their lives. But what about the flawed characters with the depressing lives? They don’t pop up as often on the bestseller lists. Maybe we could learn more from a story of crushing failure than one of success. And maybe we could learn more from an author who pities and punishes his protagonist than one who simply idealizes him.

Ever notice how most popular novels are about compelling characters with exciting lives? We love those characters, love their lives. But what about the flawed characters with the depressing lives? They don’t pop up as often on the bestseller lists. Maybe we could learn more from a story of crushing failure than one of success. And maybe we could learn more from an author who pities and punishes his protagonist than one who simply idealizes him.

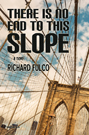

Richard Fulco, author of the forthcoming novel There Is No End to This Slope (Wampus Multimedia; March 18, 2014), tackled this subject and a few others with Claire McKinney.

Claire McKinney: In what ways have you been involved in the artistic world as a writer and as a musician?

Richard Fulco: As an undergraduate, studying English literature, I fancied myself a singer/poet. When I lost my voice and my confidence, I turned to my fallback career—writing. I wrote plays for a while, but didn’t enjoy it as much as making music.

When did you decide to focus on writing as a career and what was your first “break”?

It’s something I’ve always done, but I never focused on writing as a career. From the time I was five years old, I was writing songs and poems. By fourth grade, I had ventured into short stories and by thirteen I had made my first attempt at writing a novel. It was a war novel. I don’t know what happened to the manuscript. My mother probably threw it out, thinking it was clutter. I still remember the protagonist’s name—Sonny Remson, a gritty, no-nonsense leader of his platoon.

I continued to write poetry in high school, but my friends or family didn’t know what I was up to. None of it was any good, and I didn’t take it seriously until my second year of college when I started playing in a band.

My first break – if you can call it that – came at the New York International Fringe Festival when I decided to adapt my play into There Is No End to This Slope.

The protagonist in There Is No End to This Slope, John Lenza, is from Brooklyn and is an aspiring writer. In what ways do you think you are similar to or different from John?

In his “Note To The Reader” in Look Homeward, Angel, Thomas Wolfe wrote, “This is a first book, and in it the author has written of experience which is now far and lost, but which was once part of the fabric of his life… We are the sum of all the moments of our lives—all that is ours is in them; we cannot escape or conceal it.”

Which of the characters in the book are based on people from your past and/or present?

Every character is based on people I have known. I’ve taken liberties, of course, stretched the truth a bit, hopefully made them more engaging and in some cases more likeable.

John Lenza says at one point that he may be too intelligent to ever amount to anything. What does that mean?

Too intelligent. We should all be so lucky. This is something John says to console himself. It’s a cowardly and elitist thing to admit and it contributes to his victimization. Lenza doesn’t buy into the crap that this world is selling, though he can’t find a way to navigate the bullshit.

The day-to-day is a grind. The nine-to-five world is back-breaking. People carry on, though; they endure. What choice do we have? Some people are fortunate to have listened to their calling at an early age. The lucky ones know that they love animals and would like to be a veterinarian when they grow up. It’s not that easy for everyone, especially creative people.

Writing doesn’t pay. Unless you’re Stephen King, most writers have day jobs. Wallace Stevens was a banker. William Carlos Williams was a pediatrician. Anton Chekhov was a physician. Charles Bukowski worked for the United States Postal Service. Franz Kafka worked for an insurance company. Much like Bukowski and Kafka, Lenza wrestles with the prospect of working a job he detests. Unlike Bukowski and Kafka, Lenza’s job as a textbook salesman stultifies him to the point that he is unable to produce anything.

Ernest Hemingway said, “Sit down at a typewriter and bleed.” John Lenza does plenty of bleeding; however, he has neither the patience nor courage to be honest with himself, to commit to the demanding work and just write. After thirty years of pretending to be a writer, he is coming to terms with the brutal truth that he might not have a proclivity for writing.

John Lenza thinks of himself as a writer, and he has a creative spirit, but maybe his artistry lies elsewhere. Maybe he should pick up the guitar again.

How do you think artists survive in a culture that is very driven by money and success?

How does anybody survive? The only way to survive, for me, is by placing an emphasis on the work. Everything else—publication, reviews, accolades and compensation—doesn’t matter. And it’s not just artists who struggle, no matter if you’re a teacher, chef, gravedigger, if you’re digging a hole, make it the nicest hole you can dig.

If you were to give John Lenza a piece of advice or a “kick in the pants,” so to speak, what would it be?

A kick in the pants? That’s not all I’d like to do to him.

Honestly, I don’t think I’d be friends with that guy. John’s a decent individual, his heart is in the right place, but boy is he judgmental and pretentious. He’s pathetic, really.

If I sat down over a beer with Mr. Lenza, I’d tell him that life is mostly about failure. Either accept that or do yourself in like Virginia Woolf, Sylvia Plath, Paul Celan. Make a choice. There’s nothing more paralyzing than languishing in limbo. Purgatory is the real hell. You’re neither here nor there. Waiting. Samuel Beckett knew the score. He’d have a great deal to say to John Lenza. Beckett could set him straight, but Lenza would never listen to him.

Leave a Reply